Written by May Digweed

Contents

Why is this important?

Suggestions & feedback

At One for the World HQ, we appreciate the complex and often challenging nature of discussing topics around extreme poverty. Sometimes it can be difficult to navigate, especially when there are opposing views on certain topics. As chapter leaders, we hope you feel comfortable asking a member of HQ for advice if you ever have any concerns regarding respectful advocacy, such as whether to use a particular image or how to phrase something appropriately. If you ever feel unsure, we would rather that you ask!

Context

International development has a deeply intertwined history with issues of racism and colonialism. The so-called "Global North" has repeatedly exploited the so-called "Global South" under disguised labels of development and neoliberalism (free-market capitalism, deregulation and reduced state intervention). Multidimensional power imbalances and colonial legacies still manifest today throughout the development sector and in foreign aid. A key feature perpetuating injustice in foreign aid has been a historical disregard for local participation and voice, despite these communities being the most knowledgeable about the unique local environment. Neocolonialism is the indirect continuation of imperialist rule through the use of political, cultural, economic and other pressures. Avoiding a neocolonial development model involves moving away from prescriptive techniques, instead focusing on community engagement and respecting the agency of recipients.

This video (15 mins) delves deeper into decolonising development:

There is still a long way to go to decolonise aid and address issues of power, race and inequality in the development sector. As an organisation, we must recognise this. However, suspending all aid while waiting for these reforms would result in millions of preventable deaths, primarily children. Hence, we are devoted to supporting cost-effective interventions that mitigate extreme poverty alongside supporting reform in international aid. We support programmes that are tailored to local communities and engaged with their recipients. For example, Helen Keller International has recognised the important role of mothers as agents for change. In Mozambique, they have established a team of local women known as Lead Mothers, each of whom works with ten other local families, educating them about the importance of nutrition for children and pregnant women. Helen Keller International also maintains "country leadership" by having a local director of the program in each country where they operate.

Recipients of the programmes we support are not coerced into receiving resources such as bednets or vitamin-A supplements. The organisations aim to be transparent and respect individuals' decisions about accepting treatment. However, there is always room for improvement. In addition to its quantitative cost-effectiveness analysis, GiveWell carries out qualitative assessments of its charities, which places great emphasis on the quality of interactions and communication between participants and program staff. The qualitative assessment also explores charities' attitudes towards mistakes and self-improvement.

Why we focus on Africa

Why we focus on Africa

Our goal at One for the World is to end extreme poverty. We believe we can achieve this through effective, targeted wealth redistribution. Our promise to you and our donors is that we constantly seek to maximise the impact of donations to avert the most deaths per dollar. This is one of the fundamental principles of effective giving: doing the most good with our limited resources.

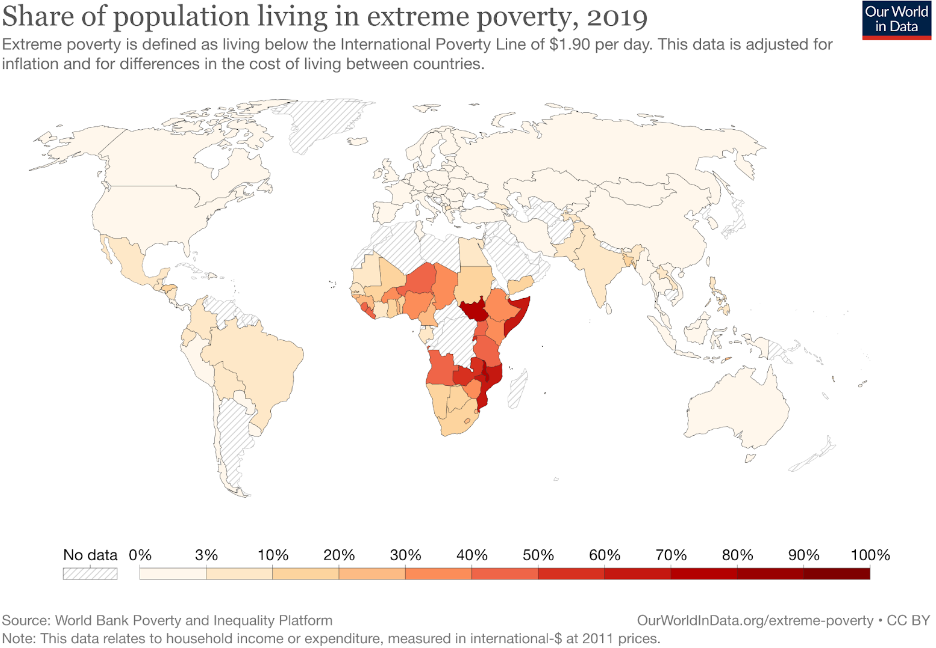

Our promise to do the most good comes with an immense responsibility to ensure our donations go to the most effective organisations and to the regions where they have the greatest impact. We use the best-in-class charity evaluator GiveWell to seek out the most cost-effective programs, which could operate anywhere in the world. Another core principle of effective giving is impartiality; we work to help those most in need. This analysis repeatedly finds the greatest impact from programmes that target extreme poverty (living on less than $1.90 per day). The map below shows that extreme poverty is heavily concentrated in Africa. Our non-profits also work in Asia and Central and South America, where there are areas of extreme poverty. We are highly aware of the dangers of portraying a whole continent in a certain way; Africa is a vast and diverse continent with a combined land mass of China, the US, Japan, India and much of Europe. However, we are dedicated to accurately reporting the problem of extreme poverty. Part of this is recognising the uneven global distribution of extreme poverty.

Images of recipients

Images of recipients

Our approach is data-driven but ultimately human-centric. We are talking about the suffering of real people, which photographs and stories can help emphasise. However, it is essential that we treat all people with the utmost respect, especially when using their images and stories to portray extreme poverty. In the past, we have used pictures without captions, but upon reflection and extensive research into responsible portrayal, we now better understand the importance of accuracy and context. Moving forward, there are three main guidelines we strive to follow for using pictures at One for the World:

1. We do not use images to show active suffering

There is cause for concern over the commodification of images of suffering and the ethics of such images. Research from Save the Children (Crombie & Warrington, 2017) found that people receiving resources from charities would prefer not to be depicted exclusively in terms of their suffering.

2. We only use stock photographs to show landscapes, volunteership, or express a general concept

3. Otherwise, all pictures are sourced from our nonprofit partners

The nonprofits ensure people in the images have consented to these images being used in marketing materials. If using these pictures, use captions that give context, such as by providing names, places and backstories.

Examples:

Cote d'Ivoire 2018, from Helen Keller International.

Health Center Salamani, Kankan, Guinea, where vaccines and vitamin-A supplements are distributed.

A One for the World tabling session.

Language

Language

| Preferred phrases | Phrases to avoid | Reasoning |

|

High-income countries / low-income countries Global South / Global North (this is the generally accepted phrasing in the development sector, but there are some reservations, perhaps consider using "so-called Global South" and "so-called Global North" instead) |

Developed/developing countries Third world |

The developed/developing dichotomy is over-simplistic and implies there is a scale of development in which the so-called "Global North" is idealised. The concept of "development" is not universal, yet this implies that development in the Global South will look the same as it did in the Global North. In reality, the Global South has its own goals and ideas for development and the Global North still has a long way to go in terms of "development". The term "Third World" originated in the Cold War, referring to countries that were outside both NATO and the Communist Bloc. Therefore, the contemporary use of the term is often factually inaccurate: by this definition, Switzerland would be Third World despite being one of the highest-income countries in the world. Additionally, the connotations of the term "Third World" are dehumanising and hierarchical. It implies that people in the Global North are living on a different and superior planet to the Global South. |

| Deaths averted | Lives saved | The concept of "saving" alludes to white saviourism, which has deep-rooted histories of colonialism and racism. Furthermore, it gives too much credit to our intervention as donors and presents recipients as passive. |

|

Use specifically named countries Sub-Saharan Africa (when appropriate) |

Simplistic references to Africa | Africa is a vast and diverse continent, with the combined land mass of China, the US, Japan, India and much of Europe. We must remain cautious of the dangers of generalising a whole continent and be more specific where appropriate. |

| People no longer living in extreme poverty | People lifted from extreme poverty | The term "lifted" is passive and implies they were "saved". This alludes to white saviourism and disregards the contributions of these people in reducing their own poverty. |

|

Participants People donations are targeting |

Beneficiaries | While people receiving the donations do benefit, labelling them as "beneficiaries" is passive and reductive. It ignores their agency to independently create positive change. |

Additional resources

- An example of the adverse effects of past international development projects: India's Green Revolution: more harm than good

- Ted Talk on the ineffectiveness of foreign aid and possible solutions: Foreign Aid: Are we really helping others or just ourselves?

- Ethical guidelines for the collection and use of images and stores: Putting the people in the pictures first

- GiveWell blog post: How not to be a "white in shining armour"